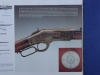

| Winchester 1873 1st Model Deluxe Carbine w/ Provenance to Prince of Wales |

This is probably one of the most historic Winchesters we've ever handled and probably ever will outside of a museum. It once belonged to the Prince of Wales who presented this carbine as a gift during his visit to India in 1875-1876. He later became King Edward VII of England following the death of his mother, Queen Victoria, in 1901. This carbine was one of a group of Winchester 1873's, fifteen rifles and fifteen carbines, that shipped from Winchester to James Kerr and the London Armoury in 1875. Winchester records indicate these were shipped with special order case colored receivers and some even had 2X deluxe burl walnut (this one included). Kerr carried out the presentation work on the guns by engraving presentations on the barrels and placing special silver plaques of the Order of the Star of India on most of the stocks. See link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_the_Star_of_India There is little doubt that these Winchesters were meant to make an impression to Indian royalty and were probably selected personally by Prince Albert Edward, an avid hunter and outdoorsman, through Winchester's English dealer James Kerr. At the time of his departure to India in 1875, the Model 1873 Winchester would have been the latest and greatest repeating rifle throughout the world. Its lever action design could fire 12 to 15 rounds of ammunition in mere seconds and the centrally primed cartridges were reloadable with a simple pair of hand tools. Most of the rifles and carbines in the group of presentations made in India appear to be between the 3,000 and 6,000 serial range. Today, six of these Winchesters (five rifles and one carbine) reside at the Royal Palace at Sandringham, England. These are listed by serial number in RL Wilson's book WINCHESTER. The carbine is pictured in the book and listed as serial number 6,618. This particular carbine is identical to it and is serial number 6,616. Furthermore, Winchester records housed at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center indicate that 6,616 was in the same shipment with 6,618 as well as several of the rifles at Sandringham. See photos. I did this research years ago for a friend of mine who had acquired this carbine and was anxious to learn more about it. There was just one thing that we could not explain. It was 1st Model 1873 Carbine in every way except one which was the stock. Normally, a carbine came with a semi-crescent shaped buttplate but this gun had a stock with a sharper crescent profile buttplate indicating that it was from a sporting rifle. It had the presentation plaque as well as several old rack numbers...often found on guns belonging to Indian royalty. It was perplexing to say the least. At some point, we removed the stock to inspect the assembly numbers. Prior to 1884, Winchester workmen placed assembly numbers on the frames, stocks, and buttplates, of all Model 1873's so that the parts could be reunited upon receiving their final finishes. The numbers on the buttplate and the stock were 475 and 475 respectively, but the frame was 409. They didn't match! From there, the wheels started turning. How could this have happened? The possibilities were endless. Could it have been a factory error in the records and this carbine was ordered with a rifle stock? Not likely as the assembly numbers would have matched. Could the Winchester dealer James Kerr switched the stock with one of the rifles when he was installing the silver plaques? Well, this was a possibility...after all the stock was from a 1st Model with a presentation plaque like the other guns. Kerr had to perform the presentation on both carbines as well as an equal number of rifles. If that were the case, it had to have come from one of the fifteen rifles in the presentation group. Then, I thought of another possibility. Perhaps, the Prince of Wales had presented this carbine along with a rifle to the same person....presumably a member of the Order of the Star of India who had mixed up the stocks during a cleaning...or perhaps it was just a preference. This was certainly possible but the theories were endless. Eventually, my friend asked me to sell this carbine for him as he was nearing retirement and wanted to begin liquidating his investments. The rifle stock always managed to hold back potential buyers as it was simply too difficult to explain the history and what ifs in the span of 1-2 minutes during a busy show. We even put this carbine in an auction only to learn that the winning bidder never bothered to pay for it. It was almost as though I was destined to keep this gun for forever as it has been in my care for several years. At some point, I got so tired of explaining the story about this carbine and the inevitable question, "Why does this carbine have a rifle stock?" that I quit bringing it to shows. Over the years, I've had many antique weapons come and go...most in a few weeks...sometimes a few months...and once in a while something hangs around for a year or two but nothing like this. It had been here for ten years. I can't explain it, but it was as though there were an invisible force at work that was not going to allow it to part my company. Perhaps that invisible force at work was entropy which I remember hearing a lecture about back in Chemistry 101 in school many years ago. As the professor explained, it had to do with the randomness of atoms or molecules constantly re-arranging themselves in a solution or a gas. Basically, entropy is the lack of order or predictability; gradual decline into disorder. That said, if there is one thing antique gun collectors can't stand, it's "disorder". We DON'T LIKE CHANGE! The less a gun changes from the time it's new, the more valuable it becomes. At some point in its history, this Winchester had been a victim of entropy. Something had been placed where it didn't belong and the chances of reversal were nil. After all, Winchester Repeating Arms had produced 720,610 Model 1873's for a span of fifty years. The thought of reversing entropy not only seemed impossible...a chance of 1 in 720,619 but it went completely against mother nature. As the years went by, I had no idea what was in play and what was coming. It happened on a beautiful Sunday afternoon in the fall of 2010. After working all week, I decided to take a break and drive to Athens, GA which is about two towns over from us. I try to get over there about once a month and visit a shop or two and then grab lunch. After a few hours, I started for home and on my way out of town, made one last stop at a book store to pick up a magazine and a cup of coffee. I wasn't in a hurry that day and so one thing led to another and I soon found myself wandering all over the store. I went down one of those aisles that has those large picture books in the discount section...some folks call them coffee table books...those big books you leave sitting around in case you have company visiting and the phone rings. Over the years, I've bought a number of gun books like this. They may not have a lot of depth but they often provide great reference material on subjects that go beyond the books in my library. As I walked down the aisle, there they were, the books on weaponry from WW2 to the Jet Age. I picked up a 1" thick book with a light green cover titled The Illustrated History of Weaponry which I had never seen before and began thumbing through the pages. "Let's see what's in this one, I thought". You name it, this book had it...from ancient armor, French shields, middle Eastern daggers, swords, flintlock pistols, and then about midway through the book came American weapons. "Now we're talking!" As I skimmed through, I flipped past what looked like a Winchester rifle with a silver plaque on the stock. A WINCHESTER! A SILVER PLAQUE???...thumbing back to it, I found the page. There on page 146 at the top was a Winchester 1873 rifle with a smoky mottled looking receiver, a first model receiver. It was turned to the left side and there at the back of the wood was a round plaque just like the 1873 Prince of Wales carbine. But just like my carbine, there was something not right about this rifle. It was a sporting rifle but it had a carbine style buttstock on it with a large rack number stamped to the side of it. It took me all of about a half a second to process this information and there it was! THAT WAS IT!!!!!! THAT WAS NUMBER 6,616's STOCK attached to another Prince of Wales presentation rifle with the same plaque and the same rack number off to the side. I couldn't believe it! It was unreal! Whoever had this rifle...well, I had their stock...the stock that belonged to their gun! I was sure of it! From the look of the book, I kind of had a feeling these photos were taken at a museum. After all, if you're writing a book that requires photography, a good museum is a one stop shop. My feeling was that given all of the foreign weaponry, the eras it spanned, and the broadness of what was in the book, was that it was probably part of a museum collection in Great Britain or Europe. I flipped to the back to learn to whom the photos were credited. On the last page of the appendices, it read "ACKNOWLEDGMENTS, unless otherwise noted, all silhouetted weaponry images are from the Berman Museum of World History, Anniston, Alabama." The book was written in 2006. It had taken four years for me to find it. These Winchester 1873's had gone from America in 1875, to England, to India, at one point I know that the carbine had been in Australia, and somehow, these two guns, with their mismatched stocks were 120 miles apart in Georgia and Alabama. In spite of the odds, that strange little round plaque was enough to catch my eye flipping through a book. 1 out of 720,619 and now I knew where it was. God does work in strange ways! Well, the next thing that had to be done was to call the Berman Museum the first thing Monday morning and tell them that I had the stock to their rifle and that they in turn, had mine. I'd like to say this all went effortlessly; that upon explaining the situation about the two the guns having switched buttstocks, the museum staff said, "Hey Mr. Wilburn, jump in your car and come right over and let's see what we can do!" That....(pause for 5 seconds right here)....1, 2, 3, 4, 5....is......not....................how.........................museums work! They simply don't! They're not gun collectors, they're historians, and they weren't about to start changing out parts on a prized rifle in their collection based on some unknown person's assumptions over the phone. Their number one job is to protect the collection they'd been entrusted to oversee. As much as I was excited about reversing the entropy and correcting what had happened to these two rifles, I'm pretty sure the only disorder and entropy they perceived was ME! After all, what I was proposing to do was to alter a piece in their collection that had been on display for decades. What I had been thinking about for the past ten years...was all news to them. I was chaos about to enter a world of calmness and order and well, understandably, they weren't too excited at first. As the curator calmly explained to me, "I've been here for twenty years and the only time that Winchester has been pulled off of display was when it was photographed for the book a few years ago." Further he explained, any thought of what you're proposing (changing the stocks) would have to be brought before the board of directors which will not meet for several months." "If you'd like, I will be happy to mention it to them at the next board meeting". Well, what could I do but send a letter explaining the situation, a link to some photos of the carbine that would hopefully prove to them what I had, and WAIT! And so I waited! Waited for months and months and pretty soon a whole year had gone by. During that year, my friend, who owned the Prince of Wales carbine passed away and it became part of the estate that went to his wife. I must say, she was very patient about the situation was willing to put liquidation aside in order for us to try and correct this piece of history. The next year, I took the carbine with me on my way to the Tulsa show in 2011 in hopes that staff at the Berman Museum would get the wheels turning and it did. Once they met with me, saw the carbine for themselves, they began to realize that what I wasn't totally off my rocker or up to something. Still, the job fell upon them to get others on board. My perspective changed a bit too. When I walked into the gallery that , I quickly realized why they had been so reluctant to entertain my proposal. Their Prince of Wales 1873 rifle was quite literally the very first gun you saw on display...it was front and center inside a large case on display with an ivory stocked Winchester 1866. They had a world class collection of weapons so the fact that this rifle is the first thing they wanted you to see spoke volumes in terms of its importance within their collection. Another year went and the wheels kept turning in the right direction. In the fall of 2012, the board of directors agreed to a meeting in which both rifles would be inspected and I would be allowed to present my case. I arrived with the carbine that day with my RL Wilson book, the Cody Letter for 6,616, a set of screw drivers, and my Winchester Bible, The Winchester Book by the late George Madis. I was met by the museum staff and Colonel Joel Denney who was on the Bermen Museum board of directors and had been authorized to make an exchange should it turn out that I could prove my case. The rifle was removed from its display case and placed on a long table along with the carbine. They looked identical...as though they had been in the same room their whole lives. The receivers were dark and smoky...the varnish on the wood turned to a deep red. You could tell these two rifles had spent a good portion of their lives together and suddenly, that theory in the back of my head about Prince Albert Edward presenting both the rifle and carbine as a pair to the same person...most likely someone very high up in the Order of the Star of India, was completely plausible. Both guns even shared the same small rack numbers on their stocks and buttplates proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that they had been owned by the same person. I purchased my first Winchester 1873 when I was thirteen years old and had studied them ever since. If ever there was a time when that effort could be put to some good in order to correct a wrong somewhere in the past, this was that moment. So I presented my case, first establishing that what I had was one of the Prince of Wales carbines...the engraved inscription, the plaque, the serial numbers in Wilson's book which corresponded to the same shipment and order number as 6,616. Then, I explained the differences of a rifle to a carbine...via help of Madis' book! Finally, Colonel Denney asked, "OK, so we know you have a Prince of Wales gun...but how do we know that your wood belongs on our gun and vice versa?" And there came the crux of my little presentation...assembly numbers. Mine didn't match and if I was correct, neither did theirs. My frame was stamped 409 while the stock and buttplate are 475. "If I'm right, and these stocks were switched, I can tell you what the numbers on your rifle will be without seeing them". My prediction was that their stock and buttplate will read "409" while your frame will be stamped "475"." I felt like a magician in the middle of a card trick. I had been waiting to say this for three years and now it was time to find out! And so we took the stock off the carbine and read the numbers. Next came the rifle...only it was very reluctant to release its stock courtesy of a loose mainspring. I tried my best to work the stock carefully off the tangs and with a tug from Colonel Denny, the stock finally came off. The rifle's now-released carbine stock read "409" and the frame was stamped "475"...just as we had hoped. They had been switched and we all realized the gravity of the moment with a roar! It was an amazing moment for all of us. Against what seemed to be improbable odds, we had successfully reunited not one but two Prince of Wales Winchester 1873's with their original stocks and one tiny bit of disorder had been reversed in the universe! It was magical moment. The rifle was carefully placed back in its showcase only this time, for the first time in 100 or more years, it was with its original stock and buttplate. My carbine looked right too looking more like a true saddle ring carbine, especially now that it had its original 2X burl wood back in place. Some months later, I stopped by the Berman Museum again and was surprised to find our little event written up in the Museum's quarterly newsletter. When time permits, I will try to add a few of the photos I took as well. Since that day, I've been allowed to take some time and enjoy this little carbine. It is time to move on and finally find this Winchester a home or museum where it can be looked after for years to come. If you feel that you have what it takes to be this carbine's new caretaker, please feel free to contact us. Item# 8207 SOLD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|